Abstract: The field of Enterprise Architecture (EA) is rapidly evolving why there is a need for

increased professionalization of the discipline. Therefore, understanding the profession of the

Enterprise Architects in enterprise transformation and development becomes important.

However, there are very few empirically based studies which have reflected these professionals

within their work domain of an every-day business. The purpose of this paper is to increase our

understanding of how the Enterprise Architect’s practice their profession and in addition, to

study how these professionals describe their occupation. Five different topics are of particular

interest to portraying the occupation of the Enterprise Architect's profession; the role,

competence, power, style of acting and main focus. The research is a descriptive study based

on interviews with Enterprise Architects in ten large Swedish organizations. In conclusion, the

architect is considered as a proud individualist with an entrepreneurial vein who endeavor

consideration, reflection, and the guidance capability.

1. Introduction

The discipline of Enterprise Architecture (EA) has evolved since John Zachman introduced his

Framework for Information System Architecture in 1987 (Zachman 1987). EA is considered as

a general approach to aligning business and IT within an organization (Langenberg & Wegmann

2004). Today's challenging business world and the increasingly rapid technological

advancement requires additional demands on organizations' resources to act strategically and

use IS/IT for development for business improvements and new business opportunities. In a

recent study of EA research, Simon et al (2013) conclude that the increasing interest in EA is

driven both by practitioners and academics. As EA has become increasingly important for large

organizations, a new organizational profession has emerged as Enterprise Architects (Strano &

Rehmani 2007). The capabilities and abilities of the Enterprise Architect are essential in

promoting EA within an organization and facilitating architectural development (Perks &

Beveridge 2004). An Enterprise Architect is intended to be the organizational guide for an

accurate balance of the technology utilization and its costs (Potts 2013). Therefore,

understanding the profession of the Enterprise Architect in enterprise transformation and

development becomes necessary due to complexities of environmental contingencies and

interdependent business relationships. Previous research related to the Enterprise Architect

profession has mainly focused on defining the role (Strano & Rehmani 2007), how the role is

changing (Gøtze 2013), and responsibilities and competence requirements (Steghuis & Proper

2008). EA Frameworks, such as TOGAF, defines the role, responsibilities and skills of Enterprise

Architects (The Open Group 2011). However, few empirically based research studying the

professionals within their work domain of an every-day business.

The purpose of this paper is to increase understanding of how the Enterprise Architects practice

their profession and in addition, to study how these professionals describe their occupation.

The intention is to accomplish a descriptive study on large businesses in Sweden. Our research

question reads: What characterizes an Enterprise Architect's profession today and what are

these professionals’ primary ambitions?

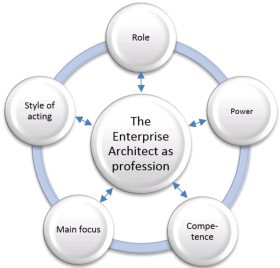

Based on an initial literature survey, we found five different topics of particular interest in

portraying the occupation of the Enterprise Architect's profession; the role, competence, power,

style of acting and main focus. The empirical research was conducted through ten semi-

structured interviews with respondents from ten large Swedish organizations. Four

organizations were public and six were private with an average of 30.000 employees, within a

range of 1.200 - 95.000 employees. The ten respondents were all senior architects and

practicing within an EA function on a daily base, though some of them without an explicit title

of Enterprise Architect. Six of the selected respondents are members of a Swedish professional

Enterprise Architect network. All interviews were conducted as live meeting at the respondent's

workplace, lasting on average 80 minutes and were digitally recorded.

2. Research model

The intended focus of this study is the Enterprise Architect as a profession. An extensive

literature survey was initially performed and where the result forms the basis of the research

model. The result from the literature survey showed that there are five different topics, which

are particularly interesting when portraying the occupation of the architect's profession; the

role, competence, power, style of acting and main focus. The interview questions in the

empirical study have been derived and grouped by the five topics according to this research

model. The knowledge base achieved in the study of the Enterprise Architect’s professional field

is described in this section.

2.1 Role

A central aspect of studying a profession is its role and its description. In several organizations,

the role description aims to clarify the employee's commitment and engagement. There are no

legal or regulatory criteria that strictly defines the role and what qualifications and credentials

are necessary to the Enterprise Architect profession (CAEAP 2012). Since EA is an evolving

discipline, the role of the Enterprise Architect is continuously changing (Bredemeyer & Malan

2004) and the role will become ever more important in the future (Gøtze 2013). Today, the role

includes multidimensional organizational disciplines such as change agent, communicator,

leader, manager and modeler (Strano & Rehmani 2007) but the role's composition and

abundance can vary depending on the organizational size (Roeleven & Broer 2009). The main

tasks of the Enterprise Architect’s role are to align IT operations with business strategic goals

by managing the complex set of interdependencies and furthermore to communicate and

maintain an agreed business strategy (Strano & Rehmani 2007). Nsubuga et al (2014) argue

that especially during strategic situational and design analysis, the Enterprise Architect plays

an essential role.

2.2 Competence

The Enterprise Architect’s competence can be described in terms of relatively extensive

requirements in both personal and professional skills (Gøtze 2013). The architect’s competence

should embrace several different areas and include skills in both business, technological,

management and the social disciplines (Tambouris et al 2012). The architect must have the

accurate knowledge, insights, attitudes and behavioral skills, and have the ability to apply

these in their profession (Wagter et al 2012). Since the profession is continuously working with

the creation of an architectural design, the knowledge of modeling is a core competence (Potts

2013). Steghuis & Proper (2008) highlights the top five intermediary competencies for the

Enterprise Architect as skills: analytical; communication; negotiations; abstraction capacity;

and sensitivity empathy. Meanwhile, Hsin-Ke & Peng-Chun (2012) argue the competence as a

collection of related abilities, commitments, knowledge, and skills that enable a person to act

efficiently. Another core competency is the ability to maintain, in both a long- and short-term

strategic alignment, between the business model and the operating model with mitigating risks

(CAEAP 2012). Skills as being a communicator and negotiator are crucial for the profession to

build trust among the stakeholders concerned (Wagter et al 2012). A common and shared

language within the organization is preferable in essence to sharpening the alignment process

(Sidorova & Kappelman 2011).

2.3 Power

The Enterprise Architect’s power in terms of authorization, empowerment and responsibility, in

both an organizational and a task-oriented way, are central when performing in a successful

way. The profession must also have equivalent power relative the liability and the

responsibility. Different authors within the academic literature describe this responsibility

differently and highlight diverse responsibilities as the most important for the EA profession.

Steghuis & Proper (2008) point out that there is no universal set of tasks and responsibilities

for the role of the Enterprise Architect. Unde (2008) illustrates the responsibility of

implementing the organization’s vision and strategy for IT. This responsibility includes defining

the standards and guidelines, and composing a governance mechanism to align implementation

to the agreed standards and guidelines.

2.4 Style of acting

The successful Enterprise Architect seeks according to Bredemeyer (2002) proactively for a

network of relationships where the collaborative incentive is to form the mutual objectives

through partnering, conferring Bahrami & Evans (2010). These shared aims will induce the

proactive enterprise transformations where the dynamic capabilities will evolve (Abraham et al

2012). Grant & Ashford (2008) have found proactively behavior at work could be distinguished

as in-role or as extra-role, where the in-role behavior determine what is expected, while the

extra-role determine the efforts by the individual to strengthen its role by widening the

individual’s enterprise. Proactivity is a readiness for planned but also unplanned changes to the

environment while considering the evolvability, vigor and elasticity of the available solutions

(Dencker & Fasth 2009). Dikkers et al (2010) advocate the responsibility of management to

foster the organization in the proactive manner contrasting the reactive. Nevertheless, a

request for proactive behavior may disguise an assignment of delegation (Sinclair & Collins

1992). Nonetheless, the deadlines and time to achieve a task is to be synchronized among the

stakeholders involved, to obtain temporal dynamics (Weiner et al 2012).

2.5 Main focus

The business domain has expectations on EA as being the solution to the current problems

while there is vague consistency in the problem description nor how the resolution should look

like (Burton 2010). In contrast, the business domain could hardly understand why the IT

domain suffering in the delivery of benefits to the business, i.e. the productivity paradox

(Brynjolfsson 1993). Quietly, the heavy cost cutting in the ICT domain has been going on for

years (Harris 2004). Though, architecture is considered a core business competence, the

balance between the business and IT domains are rare (Bredemeyer & Malan 2004). Ross

(2006) claims that the IT assimilation of the business domain is essential for the organization,

while some organizations has assimilated the IT department into the business, comprehended

as core for a future success (Steiber 2014). Bytheway (2014) advocates investing in know-how

where technology is ubiquitous, and border lines on the micro and macro perspectives are

dissolving opening for the globalization to come. Although a single Enterprise Architect could

gain benefits for the organization (Meyers 2012), still a critical mass of the Enterprise

Architectural team is necessary to attain efficiency for the architecture (Short & Burke 2010).

In this light, Luftman (2000) dispute the maturity of the domains to obtain efficacy. The

organizational ambidextrous effort to monitor and control the organization is multi-dimensional

and will involve considerations, among others, as a balance between anarchy and despotism

referred to by Lilliesköld & Taxén (2008) and efficiency and flexibility described by (Adler et al

1999).

3. The Enterprise Architect Profession in Practice - Empirical Results

The purpose of this study is to explore what characterizes an Enterprise Architect's profession

today and these professionals’ primary ambitions. The retrieved empirical data from the

respondents' answers during the conducted interviews are presented and analyzed by the

characteristics presented in figure 1.

3.1 Role

The role primarily focuses on questions concerning how the respondents’ professional job

description is compiled and to explore what kind of working tasks the architects practically

work with on a daily basis. Several of the respondents have a role description of the profession

that directly reflects decomposed objectives of the organizational EA mission. This description

is often based on a mission such as govern IT but also as performing tasks within the

application landscape and information management. One respondent describes the mission

within the role as “ensuring that the changes taking place in the IT landscape, IT services, and

IT systems are in agreement with our long-term strategies, goals and principles".

A great number of respondents state that their organizations have no specific measurement

tools to determine how efficient their work is carried out. One of the respondents is measured

on the primarily cost-saving basis while the majorities are evaluated by vague EA performance

indicators only. The results of the study show that it is not uncommon that the respondents

have other parallel assignments besides direct EA and some respondents estimate that they

periodically work more than half their time on non-direct EA activities. Several respondents

argue that the complexity of the role reflects the maturity of the organizational EA where one

of the crucial factors is the time that EA, as a function, has existed in the organization. Most

respondents consider that their EA function is relatively well established within the organization

and consequently that their role description is well defined. Several respondents consider the

Enterprise Architect profession as superior to other architectural roles. A substantial part of the

interviewed architects regard a CIO's position as a natural next step in their career.

3.2 Competence

The interviewees responded substantially identical in terms of the most important competence

for the Enterprise Architect profession. Several respondents describe business knowledge, the

processes and their interactions involved as a core competence of the profession. One

respondent describes what is important in terms of core competencies as "it is necessary to

have good knowledge about the company and its processes while knowledge about IT, is not

very important". Communication skills are argued by several respondents as a critical

competence to be an effective Enterprise Architect and needs to be able to articulate, relatively

abstract details of the strategic plan from various perspectives to different stakeholders in

accurate terminology. Another key skill that was mentioned during the interviews was the

managerial skills in terms of both understand how formal and informal decisions are made.

None of the respondents states certification requirement within a framework as a core

competence, although several respondents indicate that framework and modeling are

important skills within the profession. Almost all respondents describe continuous acquisition of

knowledge through academic studies, participate in forums, read trade magazines, visiting fairs

and collegial networking as important to be able to develop themselves and the business within

the EA field.

3.3 Power

The power as aspects of the profession is surveyed by questions concerning the capacities of

an authorization, responsibility, and obtainable resources. Several interviewed architects state

that they have a relatively comprising power that is in most aspects consistent with their

professional responsibilities. The architects describe they have a considerable degree of

freedom and full mandate to make decisions concerning architectural issues, even if they have

to take general directions into accounts, such as IT security, data privacy, compliance, and data

retention. However, when an architect becomes aware of a lacking project that does not

conform to the agreed architecture, most architects have not the power to alone stop such a

project. In these cases, a discrepancy report is created and escalated to decision-makers with

more power. This responsibility can be illustrated by the citation from one of the respondents

as "I prepare and give my technical point of view in the technical part. Then we have another

party where the formal decision is taken, and there is only the CIO member of". The

interviewed architects can be considered as satisfied professionals in terms of available

resources. None of them expresses an explicit desire for extensive resources in terms of more

time, increased budget, more accountability and need for improving education.

3.4 Style of Acting

The Enterprise Architect has a vision of acting in a proactive manner while the circumstances

and the organizational culture will force them to act reactively upon the every-day occurrences

and tasks. The architect spends a significant part of the work in promoting EA; nevertheless,

organizational initiatives to enterprise transformation give rise to incompliance with the EA.

This weakness could originate from lack of EA knowledge by the transformation project’s

members or by conflicting objectives. Nonetheless, these findings will induce a controlling style

of acting for the architect, i.e. reactive approach, while most architects interviewed are strictly

rejecting such attitude. The mission of the architects seems to focusing a transformation of

knowledge to colleagues in an effort to reduce complexity aiming to reduce the architect’s

workload on acting reactively upon misbehavior from the organizational members from an EA

perspective. Quite a few respondents report their work on the one hand as mainly problem-

solving and less problem-finding. On the other hand, a few respondents see their work as

primarily business oriented enhanced with technology utilization. Allocating time for

consideration and reflection is essential to some architects; thus, the lack of architectural

resources will force the architect to act reasonably hands-on. The architect seems to desire the

proactive habit in favor of reactive work while circumstances will force them to occupy a

particular position to correct and re-direct transformational initiatives in a late stage.

Accordingly, one respondent states “reflection is an important part of the architects work”.

3.5 Main Focus

Several Enterprise Architects, identify the organizational culture as impacting the EA and vice-

versa. The architectural work is sometimes performed as an undercover, disguised in other

words accepted and understood by the organization. However, the widely held attitude derived

from the respondents’ depiction, is that they interpret their position as balancing the

requirements from the IT domain and the business domain in a conscious manner. Commonly,

the architects emanate from the IT domain, with a previous clear IT role, but have

progressively adopted the role as part of the business domain. Indeed, the organizational pace

as a capability between the IT and business domain is of importance. For some organizations,

the EA has been developed to a level of an ivory tower, and then rejected by the organization

due to preventing the organizational innovation capabilities. Other organizations have

established a council with members from the EA function and corporate innovation team to

balance the structural EA in an aim to increase speed from various change initiatives. According

to one referent “if the accurate individuals are meeting, powerful outcome occurs”. This hint

social interaction is crucial to success.

4. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the five characteristics presented in figure 1, to explore what the

Enterprise Architect professionals do.

4.1 Role

Despite there is no sanctioned framework available to define the profession as Enterprise

Architect (CAEAP 2012), the studied architects have similar working issues, recommend similar

solutions and think significant alike in several aspects. They are the guardian, counselor and

mediator and acts by a pragmatic ideology. The most obvious differences between the

respondents can be traced to dissimilarities, which derive from different organizational settings

and the level of maturity that EA achieved within the organization. The description Strano &

Rehmani (2007) offer the profession in terms of what the architect needs to understand and

articulate the capabilities of the organization as well as the capabilities required to implement

the goal of the business, which has been verified in this study. This study confirms the

assertion that the role is changing as new technologies and features are introduced to the

organization, like Bredemeyer & Malan (2004) argue. A few interviewed architects describe

their role to a large extent containing the task of finding new solutions for the future while

most did not consider that this task was clearly defined in their job description. Almost all

respondents described, however, that one of the main tasks was to identify areas for reuse of

already existing resources as central to the role.

4.2 Competence

Regarding the desired competence for the profession, the respondents answered almost

consistently that the most important skill is to understand the business, in addition, to be a

good communicator and to be able to manage and work according to the established IT

strategy. Numerous existing research states that communication skills are crucial for the role,

and the respondents confirm this statement. A most interesting finding in this study is that this

knowledge is vital in promoting the EA function within the organization to strengthen the EA's

ability to success. Another interesting finding is the fact that several of the researchers mention

Change Management as a core competence while none of the respondents expressed this as an

essential skill. Just like Potts (2013) argues, the interviewed architects verify that the

knowledge of modeling and architecture design is a core competence. The respondents state

additionally that during the recruitment of a new Enterprise Architect, a certification or

experience in a particular framework is not essential.

4.3 Power

Steghuis & Proper (2008) present an extensive list of diverse responsibilities an Enterprise

Architect should possess, and our understanding is that the interviewed architects'

responsibility areas correlate relatively well with this description. An interesting finding is that

the responsibilities described in the academic literature often concerns areas, which mainly

relate to the architectural responsibilities within an EA/IT Governance area in terms of creating,

applying and maintaining the current application landscape within the organization. The

empirical study shows that the architect’s responsibility extends beyond the direct EA issues

and concerns responsibilities such as promoting and supporting organizational innovations and

to promote EA as an organizational service offering. A great numbers interviewed architects

describe themselves having the full power to decide within the architectural area, but their

decisions can relatively easily be circumvented since a recommendatory nature primarily

characterized the role's responsibilities. Several respondents clarify that the area of

responsibility and power should not be associated with an organizational police permitting

authorization or actively searching for scapegoats who violate the architectural guidelines. A

distinctive feature of the respondents is their desire to be positioned higher up in the

organizational hierarchy. Thereby, their role might be strengthened as a strategic capability.

4.4 Style of Acting

Temporal dynamics has been confirmed in some organizations, where the respondents

determine the pace not just on transformation speed, but also in the adoption and the balance

of a proactive and reactive manner, as key to success. The organizational culture and the habit

of the managerial style will impact the inherited pattern of acting proactively or reactively to

the concurrent circumstances. Proactivity as a starting point for new initiatives to obtain a new

state in the organizational development is quite evident to the respondents in this study. For

some organizations, the proactive behavior of the architect may address delegation where

current assignment for the architect should have been requested elsewhere. The architects’ in-

role reactive approach could be distinguished as reacting to the concurrent enterprise and IT

strategy while the in-role proactiveness in anticipating shortcoming course changes in strategy.

The architects’ extra-role as the reactive approach might be present while the architect is

forced to police utilization of incompatible business approaches and actions. The extra-role as

proactive, suggest new technology advantage that will impact a course change in the corporate

strategy.

4.5 Main Focus

Most architects pronounce the balance between the IT and the business perspective in an effort

to bridge the two, although several architects stem from and are employed by the IT

(department) domain. For some architects, the most troublesome subject is employees

representing the business domain neglecting the supportive IT function as something that the

IT people will deal with, despite the information in the systems is supplied by them.

Nonetheless, the several of the respondents acknowledge business knowledge as key to

success. A tricky part experienced by the architects is to quantify the business value derived

from (IT) technology while important to the business leaders (Evans 2009). In some

organizations, enterprise transformation speed is prioritized while EA is considered as time-

consuming and inhibiting the innovation speed. Less evidence has been found about the clear

borderline between the IT and the business domain is dissolving, which might delay the

opening for a globalization to come (Bytheway 2014). An understanding about and correct

treatment of the office politics is essential to the architects involving the balance of dual

challenges for the ambidextrous organization. Thus, a proper wording rendering the

organizational culture and by then understood by the organizational members might have a

tremendous effect on how EA will penetrate the organization.

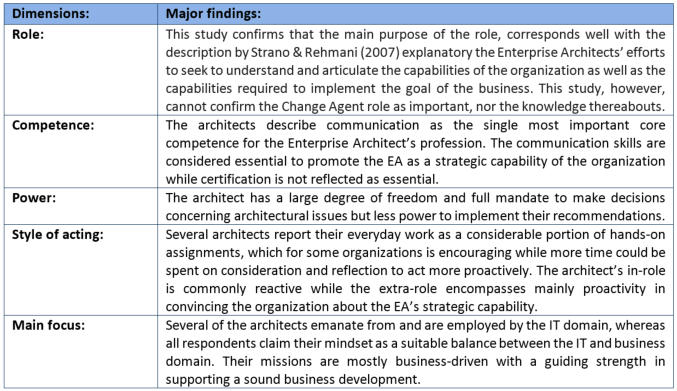

5. Summery and conclusion

This study is intended to explore what characterizes an Enterprise Architect's profession today

and these professionals’ primary ambitions. The research is performed on Swedish business

only while there is a certain interest to compare this study with a similar study in other

countries. We have characterized the Enterprise Architect profession from five topics; role,

competence, power, style of acting and main focus.

Table 1. Major findings.

In summary, the main ambition at work for the Enterprise Architect is to promote the EA where

the architects uphold the communication skills as key to success in their missionary work about

the EA’s strategic capability. The architect is considered as a proud individualist with an

entrepreneurial vein who endeavor consideration, reflection and a guidance capability. The

architects are working relatively alike within their profession. We interpret this as an indication

of that the Enterprise Architect profession is still under construction.

The Enterprise Architect profession: An empirical study

Figure 1. The research model

Page references:

Abraham, R., Aier, S. and Winter, R. (2012) Two Speeds of EAM—A Dynamic Capabilities Perspective. Trends in Enterprise Architecture Research and Practice Driven

Research on Enterprise Transformation. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Adler, P. S., Goldoftas, B. and Levine, D. I. (1999) "Flexibility Versus Efficiency? A Case Study of Model Changeovers in the Toyota Production System". Organization

Science, 10(1), pp 43-68.

Bahrami, H. and Evans, S. (2010) Super-Flexibility for Knowledge Enterprises: A Toolkit for Dynamic Adaptation (2nd Edition), Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer.

Bredemeyer, D. (2002) What it Takes to be Great in the Role of Enterprise Architect. Enterprise Architecture Conference, October 2002.

Bredemeyer, D. and Malan, R. (2004) "What It Takes to Be a Great Enterprise Architect". Enterprise Architecture 7(8). Cutter Consortium Executive Report.

Brynjolfsson, E. (1993) The productivity paradox of information technology. New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Burton, B. (2010) Enterprise Architecture Seminar Workshop Results: Top EA Challenges. Gartner Group.

Bytheway, A. (2014) Investing in Information: The Information Management Body of Knowledge, Cham, Springer.

CAEAP (2012) Enterprise Architecture: A Professional Practice Guide. Center for the Advancement of the Enterprise Architecture Profession.

Dencker, K. and Fasth, Å. (2009) A model for assessment of proactivity potential in technical resources. 6th International Conference on Digital Enterprise

Technology, Hong Kong. pp 1-7.

Dikkers, J. S. E., Vinkenburg, C. J., Lange, A. H. d., Jansen, P. G. W. and Kooij, T. A. M. (2010) "Proactivity, job characteristics, and engagement: a longitudinal

study". Career Development International, 15(1), pp 59-77.

Evans, B. (2009) "CEO-To-CIO Mandate: Quantify Business Value Of IT". InformationWeek, (1228), pp 8-8.

Grant, A. M. and Ashford, S. J. (2008) "The dynamics of proactivity at work". Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, pp 3-34.

Gøtze, J. (2013) The changing role of the enterprise architect. Proceedings - IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop, EDOC. pp 319-

326.

Harris, R. L. (2004) "IT Cost Cutting: Trends In The Trenches". Business Communications Review, 34(1), pp 47-49.

Hsin-Ke, L. and Peng-Chun, L. (2012) A study of competence of enterprise architects in higher education. Software Engineering and Service Science (ICSESS). pp

551-554.

Langenberg, K. and Wegmann, A. (2004) Enterprise Architecture: What Aspects is Current Research Targeting?

Lilliesköld, J. and Taxén, L. (2008) Knowledge Integration – Balancing Between Anarchy and Despotism.

Luftman, J. (2000) "Assessing Business-IT Alignment Maturity". Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(14), pp 1-51.

Meyers, M. P. (2012) "The Frugal Enterprise Architect". Journal of Enterprise Architecture, pp 48-56.

Nsubuga, W. M., Magoulas, T. and Pessi, K. (2014) Understanding the Roles of Enterprise Architects in a Proactive Enterprise Development Context. 8th European

Conference on IS Management and Evaluation: ECIME2014. pp 1-9.

Perks, C. and Beveridge, T. (2004) Guide to Enterprise IT Architecture, New York, Springer.

Potts, C. (2013) "Enterprise Architecture: a Courageous Venture". Journal of Enterprise Architecture, 9(3), pp 1-6.

Roeleven, S. and Broer, J. (2009) Why two thirds of Enterprise Architecture projects fail. Saarbruecken, Germany: IDS Scheer AG.

Ross, J. W. (2006) Enterprise Architecture: Drivning Business Benefits from IT. MIT Sloan CISR WP 359.

Short, J. and Burke, B. (2010) Determining the Right Size for Your Enterprise Architecture Team. Gartner Group.

Sidorova, A. and Kappelman, L. A. (2011) "Better Business-IT Alignment Through Enterprise Architecture: An Actor-Network Theory Perspective". Journal of

Enterprise Architecture, pp 39-47.

Simon, D., Fischbach, K. and Schoder, D. (2013) "An Exploration of Enterprise Architecture Research". Communications of the Association for Information Systems,

32, pp 1-72.

Sinclair, J. and Collins, D. (1992) "New Skills for Workers". Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 13(3), pp 2-32.

Steghuis, C. and Proper, E. (2008) Competencies and Responsibilities of Enterprise Architects - A jack-of-all-trades? In: Dietz, J. L. G., Albani, A. & Barjis, J. (eds.)

Advances in Enterprise Engineering I. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer

Steiber, A. (2014) The Google Model: Managing Continuous Innovation in a Rapidly Changing World, Cham, Springer International Publishing.

Strano, C. and Rehmani, Q. (2007) "The role of the enterprise architect". Information systems and e-business management, 5(4), pp 379-396.

Tambouris, E., Zotou, M., Kalampokis, E. and Tarabanis, K. (2012) "Fostering enterprise architecture education and training with the enterprise architecture

competence framework". International Journal of Training and Development, 16(2), pp 128-136.

The Open Group (2011) "TOGAF ver 9.1".

Unde, A. (2008) "Becoming an Architect in a System Integrator". The Architecture Journal, 2-6.

Wagter, R., Proper, H. A. and Witte, D. (2012) Enterprise Architecture: A Strategic Specialism. IEEE.

Weiner, I. B., Schmitt, N. W. and Highhouse, S. (2012) Handbook of psychology: Industrial and organizational psychology, Wiley-Blackwell.

Zachman, J. A. (1987) "A framework for information systems architecture". IBM Systems Journal, 25(3), pp 276-292.

External links:

Rolf Olsson | ITM-Studier | Tingens internet (internet of things) | Affärsnyttan

© Enterprise Architect, 2015.

Version 0.27, 2015-10-11